With breast augmentation being the most popular cosmetic procedure performed year after year, it’s no secret that women are concerned with the appearance of their breasts. And just as there are no two breasts that are identical, no two nipples are identical either. Circular, oblong, short, long, dark, light, pointed, flat; nipples come in all different shapes, sizes, and colors.

Flat nipples, or inverted nipples, are common and affect nearly 20% of all women. An inverted nipple is defined as one that is flat against the areola. With all the focus that is put on the breasts it comes as no shock that addressing inverted nipples is a common ask. Board certified plastic surgeon Dr. Dustin Reid of Austin offers his insight into treating inverted nipples.

What Causes Inverted Nipples?

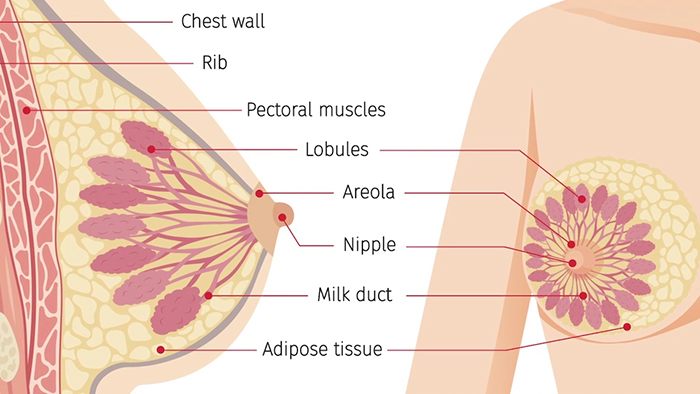

While some are born with inverted nipples and generally speaking don’t require treatment, it is possible for nipples to transform throughout our lives. What causes nipples to be inverted? “Physiologically, it is caused by the milk ducts underneath the nipple drawing the nipple inward as they contract,” explains Dr. Reid. “As to why they contract, there is no good answer.”

As stated, most cases of nipple inversion are congenital, but other causes include:

- Breast cancer

- Widening/thickening of the milk duct

- Mastitis (inflammation and infection of a clogged milk duct)

- Loss of fat in the area

Treatment Options for Inverted Nipples

Having inverted nipples usually warrants no medical attention. While breastfeeding may be affected, there are typically strategies that will allow for a mother to breastfeed. Depending on the degree of inversion, it can be more difficult. Additionally, nipple inversion can give the overall breast an aged appearance adding to the embarrassment some feel regarding the issue.

Luckily, correcting the issue is fairly straightforward. A small incision to release the ducts, allowing the nipple to gain its normal position, is one option, but there is a chance opting for this treatment could lead to reoccurrence. Dr. Reid suggests using sutures to close the space between the nipple and ducts..

Most often, treatment is available in office using local anesthesia with very little to no risk involved. “The biggest risks involved is reoccurrence, and that’s less than 2%,” states Dr. Reid.